Ada Lovelace - Prophet of the Computer Age

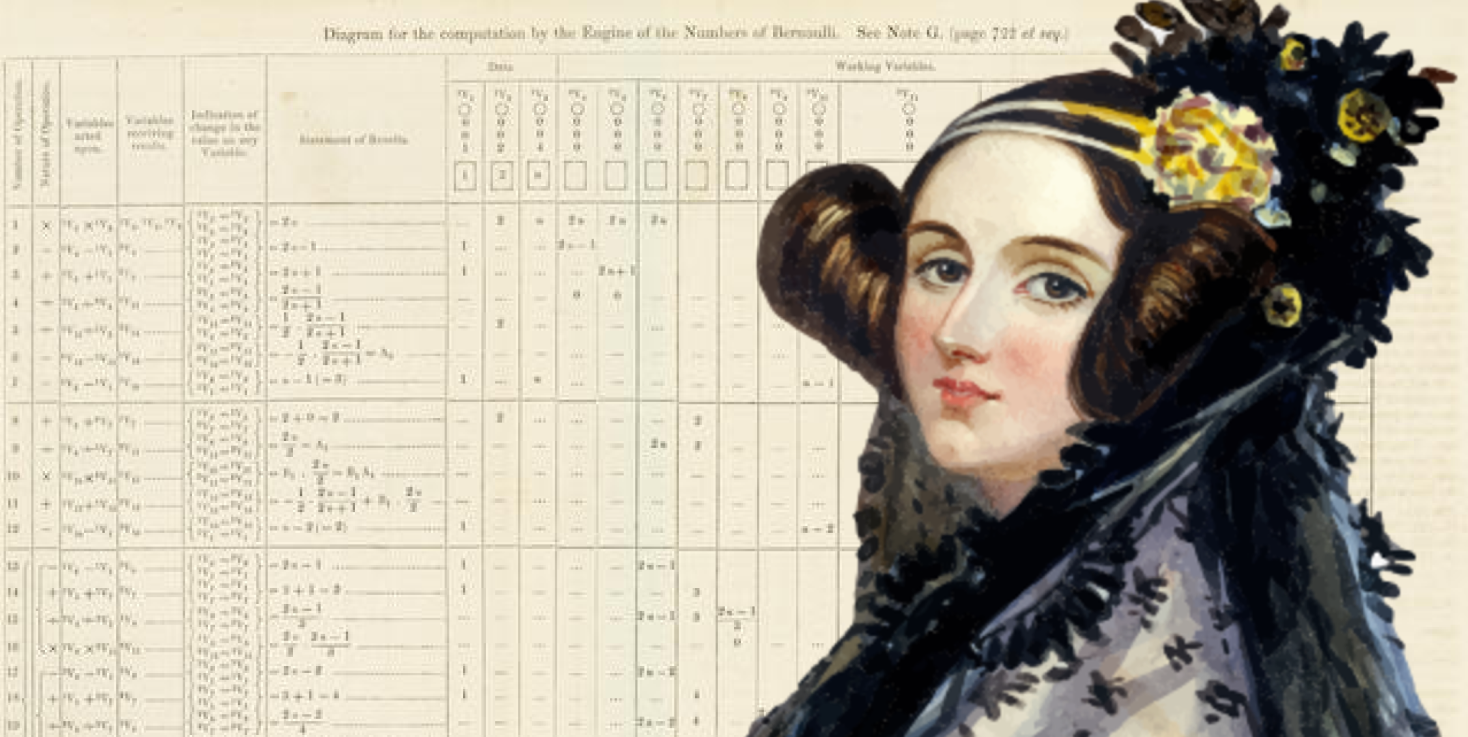

Computer science is dominated by men, yet the first computer program was written by a woman. Ada Lovelace was a remarkable woman with a short but remarkable life. A prophet of the computer age, she is an inspiration for all women in STEM.

Statistics may vary but in the world of programming there is one firm consistency - men outnumber women. In fact, in early 2020 it was estimated that globally around 91% of programmers are men. And yet, the individual credited as the first computer programmer was in fact a woman. (Fuegi and Francis, 2003) Augustus Ada King, Countess of Lovelace, (Ada Lovelace) is credited as being not only the first female programmer but the first person to ever write a paper discussing the programming of a computer. In an age where many women were treated as irrational, and their education (if they got one) was limited, Ada was an expert in mathematics and logic. Women have been involved in computing since the very beginning and it all started with a meeting between 17 year old Ada and 41 year old Charles Babbage.

The remarkable Ada was the daughter of the prestigious, and notorious, poet Lord Byron and his wife Anna Isabella Noel Byron. The only legitimate child of Lord Byron, her parents separated when she was just one month old. Three months later her father left England and Ada never saw her father again as he died in Greece when she was 8, although she remained fascinated by him and insisted that, following death, she be buried beside him. In contrast to Lord Byron, Lady Byron was a keen mathematician; an educated woman. Lord Byron was notorious for leading an immoral life, which Lady Byron in part attributed to his artistic tendencies. Thus, in an effort to guide her daughter, and prevent Ada from following in her fathers footsteps, Lady Byron ensured the young Ada was well tutored in mathematics and logic. Much to her mother's relief, Ada took well to her studies and was a dedicated student. Ada's education was far from typical. Mathematics was popular in Europe but, although interest was growing in England, it was still not considered a standard education - certainly not for a woman. This education brought Ada into contact with individuals such as Michael Faraday, Charles Dickens and Charles Babbage. It was her association with the latter which would lead to her groundbreaking achievements.

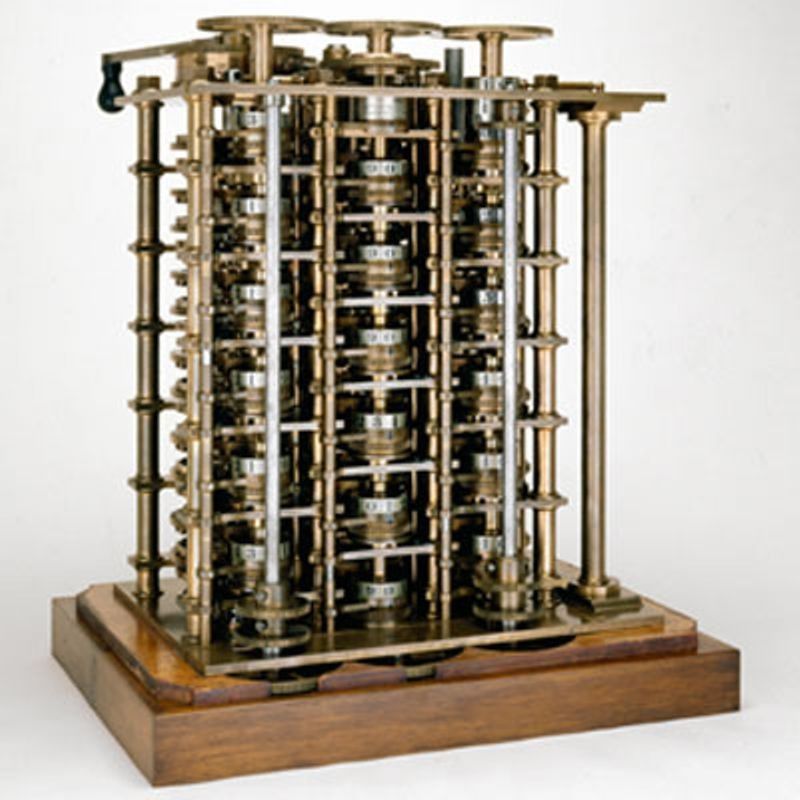

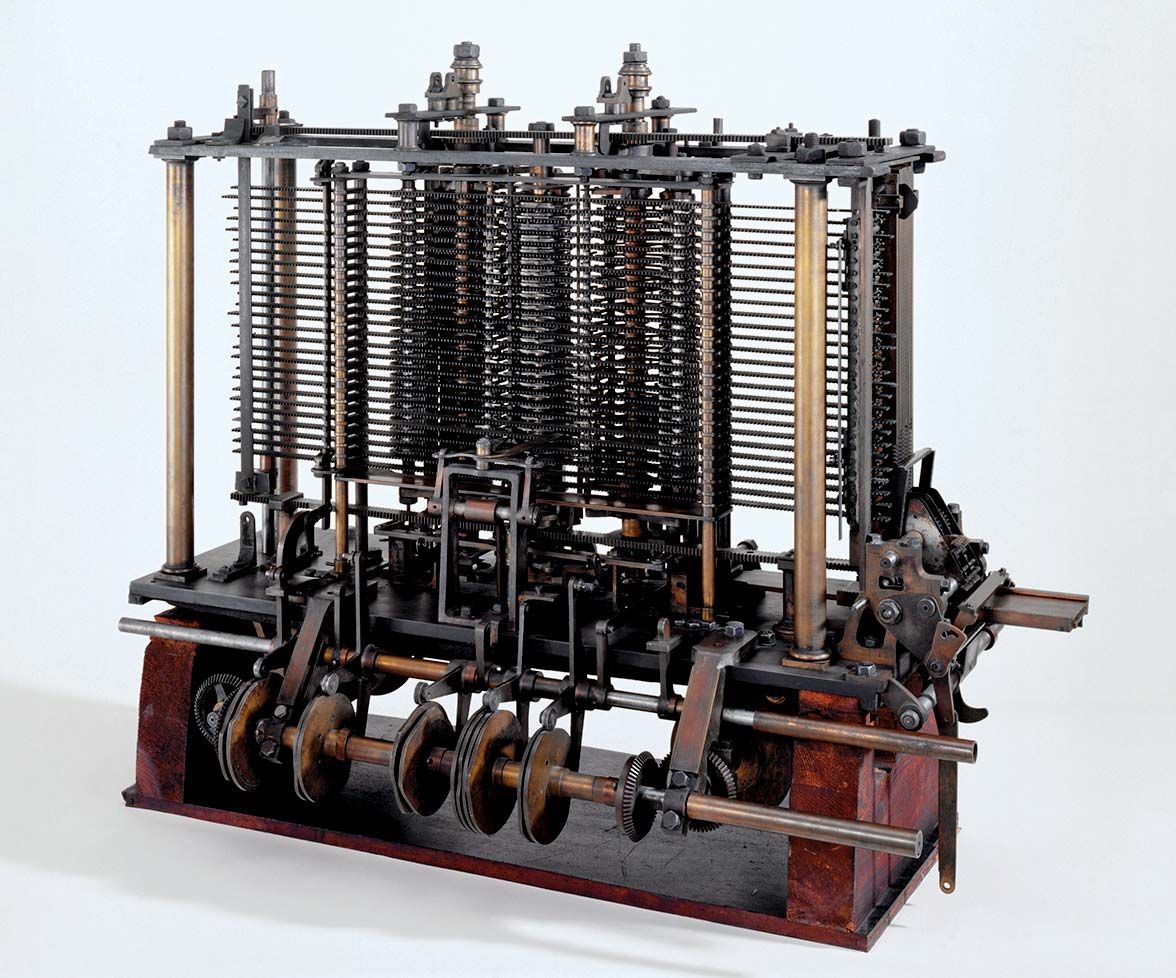

In 1833, Ada met Charles Babbage at a party where Babbage was discussing his Difference Machine. Babbage's invention was an early form of calculator which he had developed in the 1820s. The machine used punch cards to conduct more complex calculations and captured the attention of Ada, who was fascinated and followed the Difference Machine' development closely. However, Babbage decided his machine was limited so in 1937 he commenced work on a new machine - the Analytical Engine. This 'engine', which was intended to complete even more complex calculations, was demonstrated by Babbage in Italy. Present at the demonstration was Luigi Menabrea who wrote notes about the engine in French.

Ada, now Countess of Lovelace following her marriage to William King, Count of Lovelace, was tasked in 1841 with translating Menabrea's notes from French into English. (Huskey, 1980) Babbage, who had kept in touch with Ada, encouraged her to annotate the translation - adding her own comments and ideas. This translation became Ada's signature work. Throughout, she suggested that the possibility of the Analytical engine was limitless, she even imagined a world where a machine could compose music if programmed to. Altogether, Ada's translation was twice as long as the original paper and included seven additional notes. Amongst her commentary she debunked the idea (often still attributed to modern computers) that the Analytical engine was 'thinking' arguing that "The analytical Engine has no pretentions whatever to originate anything, it can do whatever we know how to order it to perform". In other words, the Analytical engine can only do what it is programmed to do.

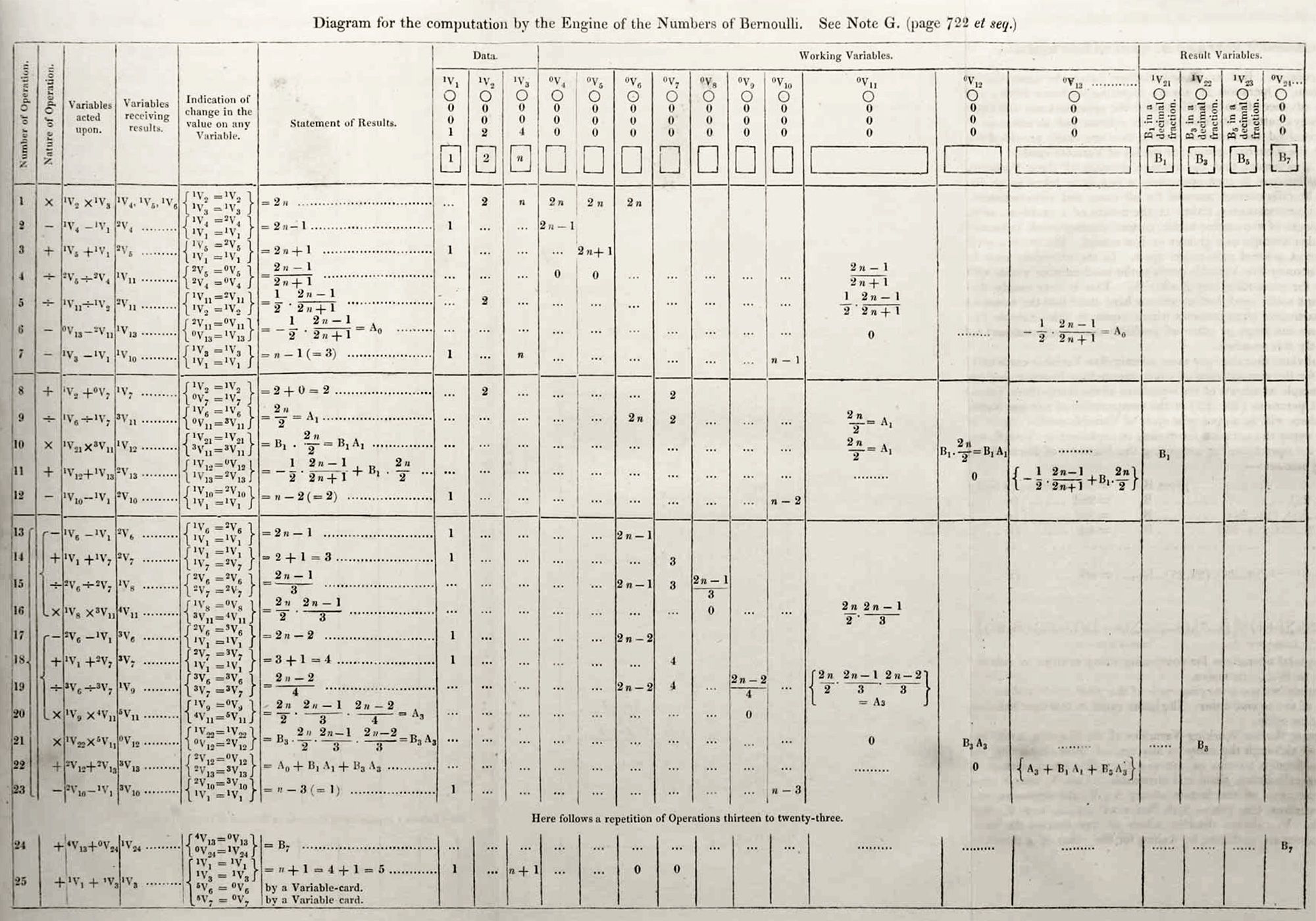

Ada's notes end with note G, which thrust Ada, perhaps unwittingly, into the history books. Note G concerns a programme for computing Bernoulli numbers. This programme was more complex and advanced than anything which Babbage himself had written for the engine. It is widely accepted in the 21st century that in note G Ada Lovelace presents the first published computer programme - a century before computers were officially invented. Ever Ada's mentor and academic support, Babbage was continually impressed by Ada's work. In a letter responding to her translation, Babbage commented "All this was impossible for you to know by intuition and the more I read your notes the more surprised I am at them and regret not having earlier explored so rich a vein of the noblest metal". Nonetheless, not all of Ada's ideas went to plan. In an attempt to help Babbage fund the building of the Analytical engine, Ada developed a system intended to predict gambling odds on horse racing. The scheme failed and Ada landed in considerable debt.

Augusta Ada King, Countess of Lovelace was ahead of her time, but her brilliant life was cut short when she died of cancer on November 27th, 1852, aged just 36. (Baum, 1986) Throughout her life, she had been fascinated by her absent father, Lord Byron, and it had long been her wish to be buried alongside him. She was interred next to Lord Byron in the graveyard of the Church of St. Mary Magdalene in Hucknall, England. She considered herself an 'analyst and metaphysician', (Toole, 1998, pp.156-157) her long time admired, Charles Babbage, considered her 'the enchantress of number'. (Wolfram, 2015) Despite her genius, her work remained obscure for decades, perhaps because of the limited practical impact of her work considering Babbage's Analytical engine was never fully completed. Her name came to light again in 1953, when Bertram V. Bowden wrote a history of computers. He hailed Ada as 'a prophet'. Although many developments were made independently of Ada Lovelace and Charles Babbage, Ada is still credited as the author of the first computer programme. Her other lasting influence was her use of a binary system in place of Babbage's decimal system. To this day, computers exist on binary. More recently, in her honour, the American Department of Defence created a coding language named ADA.

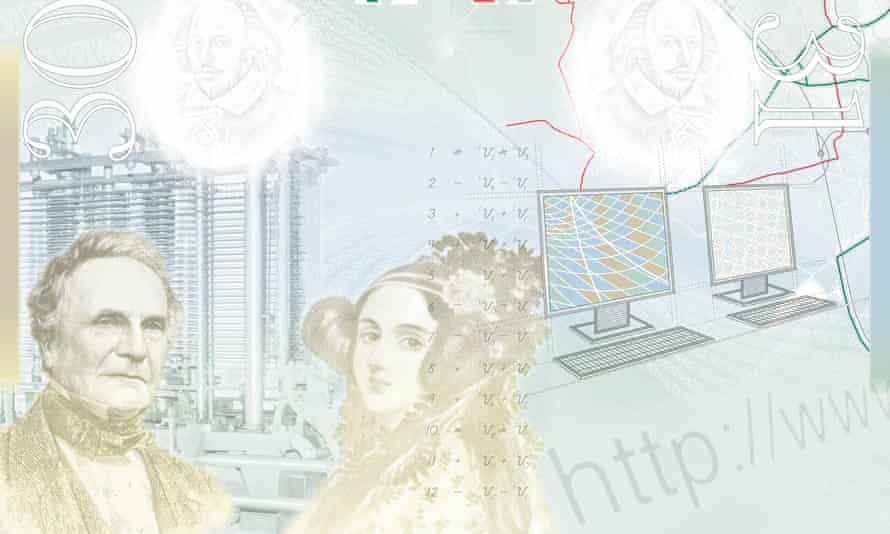

Her contribution to the world of computing has captured popular culture with her featuring as characters in books, TV shows and films. The second Tuesday in October is now celebrated as Ada Lovelace Day. British passports feature her image and buildings have been named after her. (HM Passport Office, 2018) She is heralded as an icon for women in STEM. Women were once at the core of programming, yet despite women being involved since the days of Ada, programming has become a male dominated field. This is changing. Schools in England now teach about Ada, and programmes are in place to encourage girls to enter computer programming. It is hard to not wonder about how Ada would feel about the 21st century world, full of computers and programmes derived from her own.

Find out more

References

- Baum, Joan (1986), The Calculating Passion of Ada Byron, Archon, ISBN 978-0-208-02119-9.

- Fuegi, J; Francis, J (October–December 2003), "Lovelace & Babbage and the creation of the 1843 'notes'" (PDF), Annals of the History of Computing, 25 (4): 16–26, doi:10.1109/MAHC.2003.1253887, S2CID 40077111, archived from the original(PDF) on 15 February 2020.

- Toole, Betty Alexandra (1998), Ada, the Enchantress of Numbers: Prophet of the Computer Age, Strawberry Press, ISBN 978-0-912647-18-0.

- Wolfram, Stephen (10 December 2015). "Untangling the Tale of Ada Lovelace". Then, on Sept. 9, Babbage wrote to Ada, expressing his admiration for her and (famously) describing her as 'Enchantress of Number' and 'my dear and much admired Interpreter'. (Yes, despite what's often quoted, he wrote 'Number' not 'Numbers'.)

- Huskey, Velma R.; Huskey, Harry D. (1980). "Lady Lovelace and Charles Babbage". Annals of the History of Computing. 2 (4): 299–329. doi:10.1109/MAHC.1980.10042. S2CID 2640048.

- "Introducing the new UK passport design" (PDF). HM Passport Office. Retrieved 20 April 2018.