Frida Kahlo - Turning pain into art

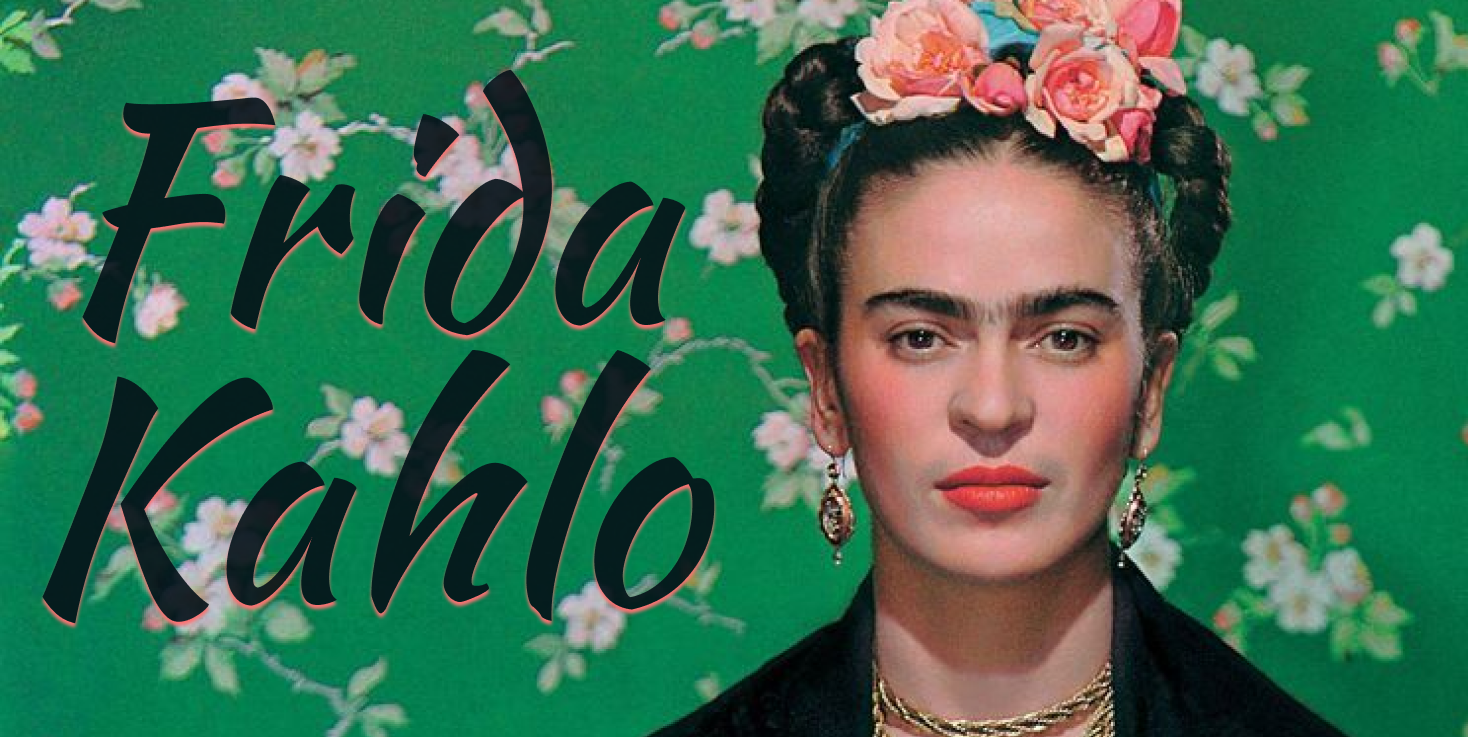

A woman who turned her pain into art, Frida Kahlo is perhaps one of the most instantly recognisable women in the world, thanks to her many self portraits. She died young, but her legacy continues to grow.

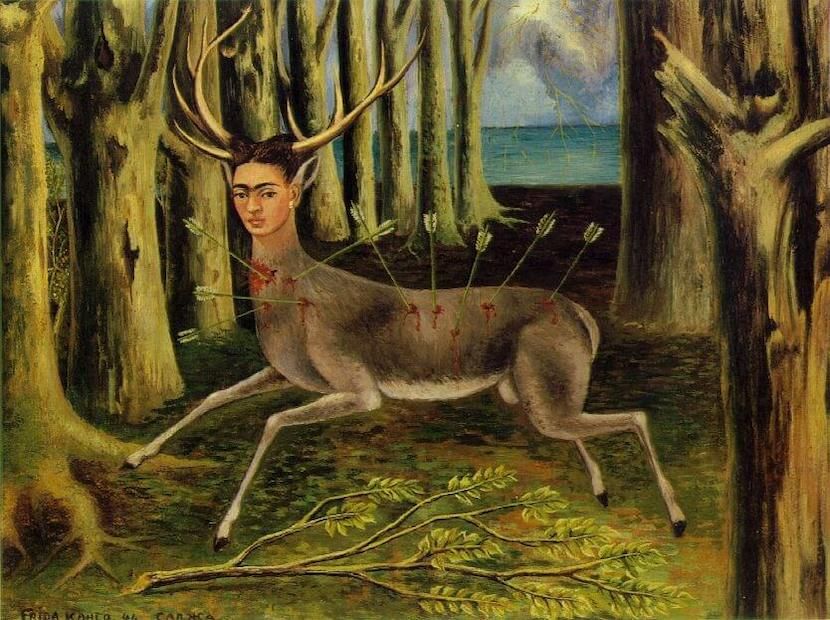

Frida Kahlo is perhaps one of the most instantly recognisable artists in the world. Her numerous self-portraits have been used across fashion - on tote bags and t-shirts. However, during her life she only became successful for the final few years before her death. Her injury at 18-years-old caused her lifelong pain and disability, her marriage was scattered with affairs and a brief divorce, and towards the end, Kahlo was plagued by depression and anxiety. Yet, she turned this pain into art. Her surrealist painting are enigmatic, and at times confusing, love them or hate them, one cannot deny they spark interest. Perhaps the key to her rising fame in recent years is because she is a symbol of non-conformity, simultaneously 'a victim crippled and abused' and 'a survivor who fights back'.

Magdalene Carmen Frieda Kahlo y Calderón (Frida Kahlo), was born July 6th, 1907, in Coyoacán, Mexico City, Mexico. Her father, Guillermo Kahlo was a German photographer who immigrated to Mexico where he met and married Matilde Calderón y González. From a young age, Kahlo faced health difficulties. Aged 6 she caught Polio which left her bedridden for 9 months. The disease damaged her right leg and foot which caused her to walk with a limp. Kahlo's father encouraged her to play football, go swimming and even wrestle (unusual sports for a girl at this time) in order to aid with her recovery. In 1922 she was one of the few female students to attend the National Preparatory School. Whilst at school she was known for her jovial spirit, love of colour, and her enjoyment of traditional clothes and jewellery. She spent her time with politically like-minded students, and she became politically active by joining the Young Communist league and the Mexican Communist Party.

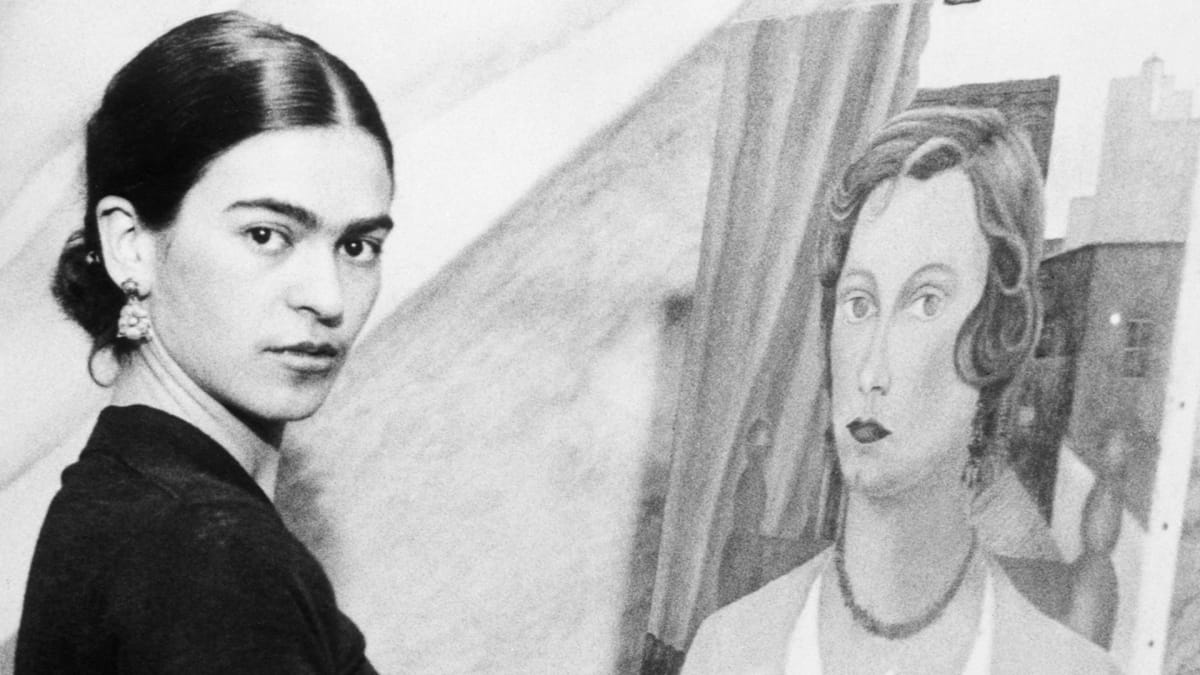

On September 17, 1925, Kahlo's life was permanently changed. Kahlo was on a bus with Alejandro Gomez Arias, a school friend who she was romantically involved with, when the bus collided with a streetcar. Kahlo was impaled by a handrail which went through her hip and out the other side. Her injuries were multiple and included a fractured spine and pelvis. These injuries would be a recurrent cause of pain throughout Kahlo's life. As a child she had ambitions to become a doctor, however her injuries put a stop to that. Following the accident, Kahlo spent several weeks at the Red Cross Hospital in Mexico City before returning home to recuperate. It was during this time that Kahlo discovered a new passion for art, and she began painting. Her mother provided her with a specially made easel, and she had a mirror fitted above her bed so she could see her reflection for self-portraits. This trend would continue throughout her life - self-portraits would become a defining element of Frida Kahlo's portfolio.

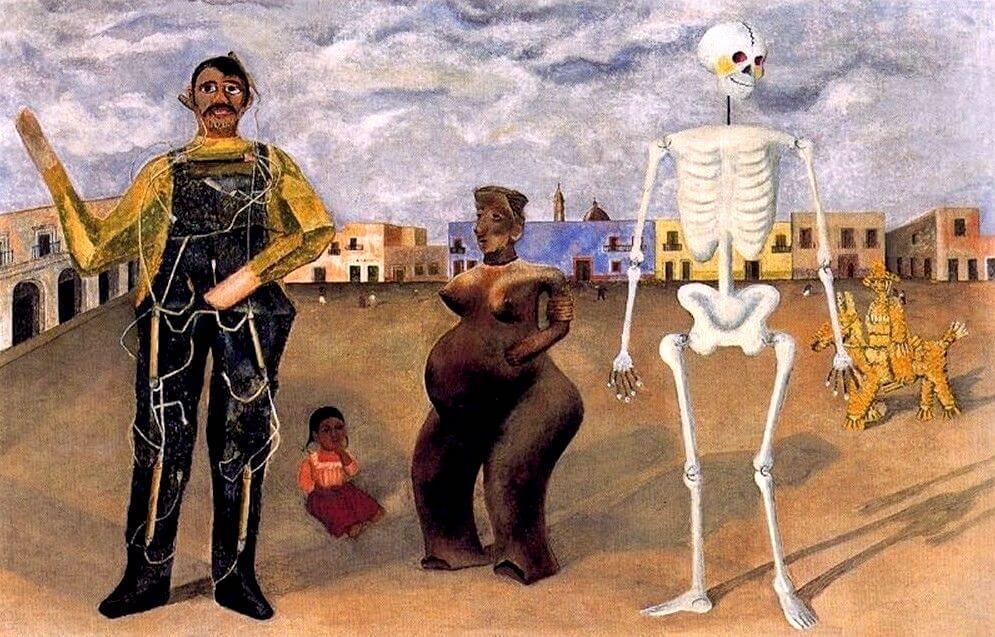

In 1922, Kahlo met the famed Mexican artist, Diego Rivera, when he worked on a project at Kahlo's school. The two reconnected six years later in 1928, and Rivera encouraged Kahlo in her artistic pursuits. The following year, 1929, Frida Kahlo and Diego Rivera were married, although their relationship was far from smooth sailing. Due to his successful art career, Kahlo followed Rivera based on his commissions. In 1930 they lived in San Francisco before moving to New York, where Rivera had an exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA). They also spent time living in New York where Rivera had a commission from the Detroit Institute of Arts. In 1933 the couple were again in New York. Rivera had received a commission from the Rockefeller family to create a mural for the Rockefeller centre however, this work of art would lead to controversy. The mural, titled 'Man at the crossroads' was intended to represent the contrasts between capitalism and communism - an idea the Rockefellers approved of. However, the New York World Telegram called the mural a piece of communist propaganda (Rivera was well known for his communist sympathies). In response, Rivera included a portrait of Vladimir Lenin within the mural. When the Rockefellers discovered this, they ordered Rivera to remove the portrait, when he refused, the whole mural was plastered over, before finished. Following this event, Kahlo and her husband returned to Mexico.

During their marriage, Kahlo and Rivera lived in separate but adjoining houses. Both had many infidelities - on one occasion Rivera had an affair with Kahlo's sister. Desperate for a child, Kahlo was devastated when she miscarried in 1934 - she never had any successful pregnancies. Their life together was by no means ordinary. In 1937, Kahlo and Rivera helped Leon Trotsky (a former senior figure of the Soviet Union) and his wife Natalia, a reminder of their communist views. The Russians stayed with Kahlo in Mexico at the Blue house - Kahlo's childhood home - and it is believed that during this time Kahlo had an affair with Trotsky. The couple were also briefly divorced in 1939, but they remarried in 1940.

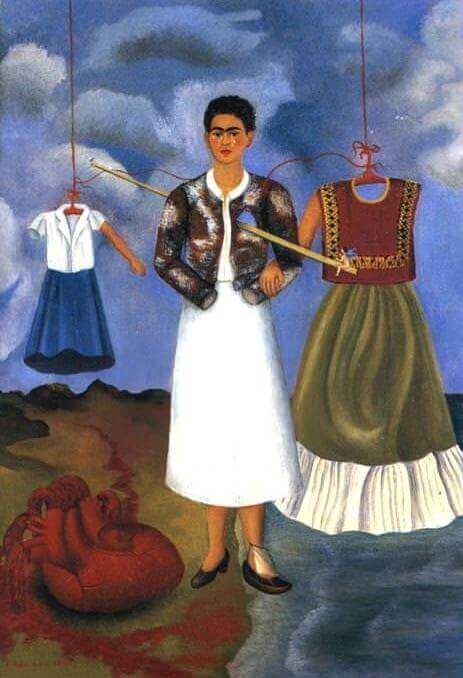

From 1937 - 8 Kahlo was very artistically productive. She produced many works of art; My Nurse and I (1937) and Memory, the heart (1937) are just a couple of the works she produced. The National Autonomous University of Mexico exhibited some of Kahlo's work in 1938, and the same year Kahlo had her first major sale. She sold four paintings to Edward G. Robinson, a film star and art collector, for $200 each. Also in 1938, Rivera was visited by Andre Breton, a successful surrealist artist who was impressed by Kahlo's work. Breton described Kahlo's work as surrealist stating it was like 'a ribbon around a bomb'. Breton also promised to arrange a Paris exhibition for Kahlo and wrote to Julien Levy, an art dealer, who then invited Kahlo to hold her first solo exhibition at his exhibition gallery in Manhattan. This solo exhibition took place in November, Kahlo had travelled to New York in October and her colourful Mexican dresses caused a sensation. She was considered the height of exotica. The reaction to her first exhibition was positive but the reviews were also condescending. An article in Time claimed that 'Little Frida's pictures...had the daintiness of miniatures, the vivid reds and yellows of Mexican tradition, and the playful bloody fancy of an unsentimental child'. The exhibition was a success with Kahlo managing to sell half of the paintings on display, despite the Great Depression.

January 1939, Kahlo sailed to Paris to follow up on Breton's promise of a Paris exhibition. However, Breton had failed to clear Kahlo's paintings through customs, and he no longer owned a gallery for her to exhibit her work at. Instead, Kahlo arranged her own exhibition at Renou et Colle Gallery. Unfortunately, she was only able to show two of her paintings as the rest were considered too shocking for display. Overall, the exhibition was a failure. It received far less attention than her show in New York, in part due to World War Two, and the monetary loss suffered forced Kahlo to cancel an upcoming exhibit in London. However not all was lost; the Louvre Museum purchased one of her paintings making her the first Mexican artist to be featured in their collection. Although the French public showed limited interest in her work, Kahlo was well received by French artists such as Pablo Picasso and even Vogue Paris decided to feature her on its pages. When she returned to the United States her work still raised interest. In 1941 she was featured at the Institute of Contemporary Art in Boston. The following year, she featured in two high profile exhibits - Twentieth Century Portraits at the MoMA and another titled First Papers of Surrealism. In 1943 her art was shown as part of Mexican Art today at the Philadelphia Museum of Art. Further recognition for her work was received in Mexico where she was a founding member of Seminario de Culture Mexicana, a committee of 25 artists commissioned by the Ministry of Public Education in 1942. The purpose of the committee was to spread public knowledge of Mexican culture and Kahlo's art was featured in exhibits in Mexico City.

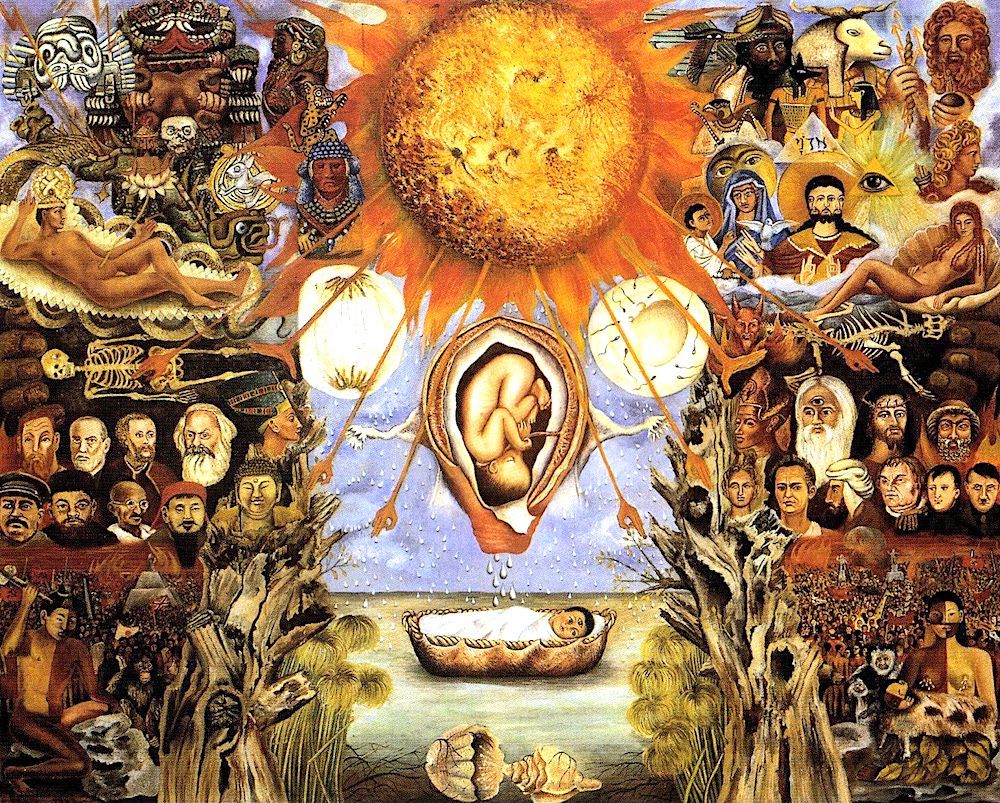

Despite a teaching position, where she encouraged her students to treat her informally and taught an appreciation for Mexican popular culture and folk art, Kahlo struggled to make a living until the mid to late 1940s. This was partly because she refused to adapt her art to her clients wishes. Nevertheless, she had some regular clients and in 1946 she won 5000 pesos as a national prize for her painting Moses (1945).

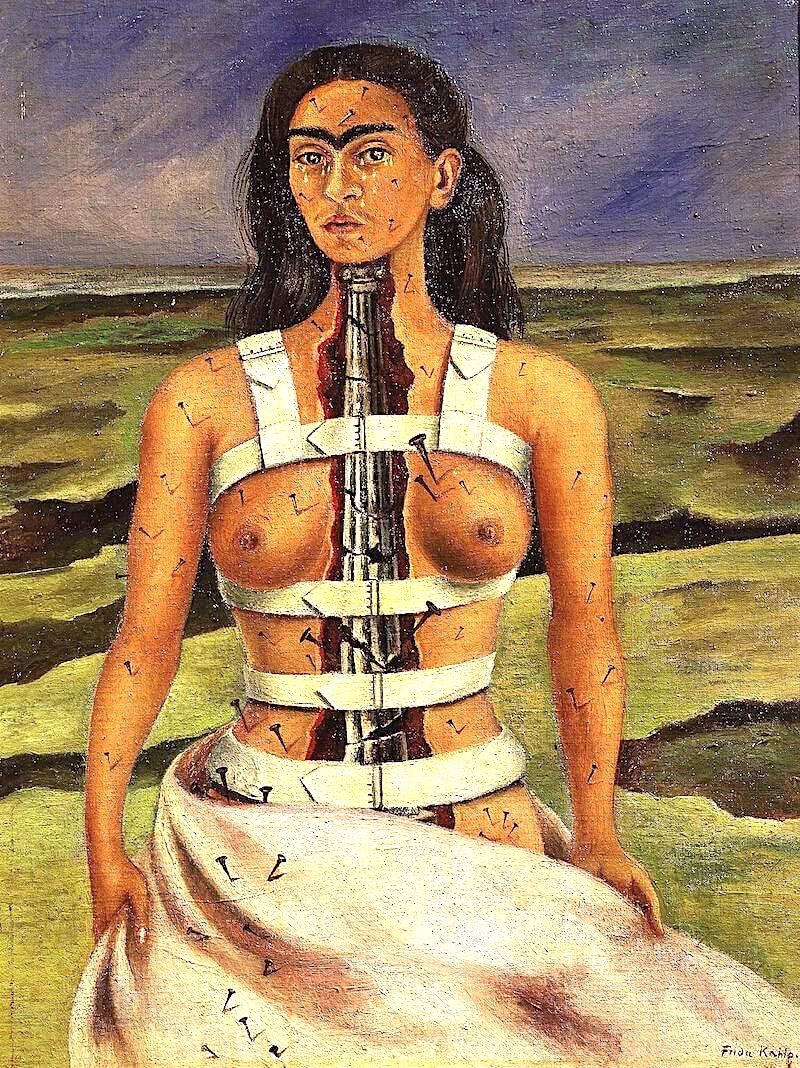

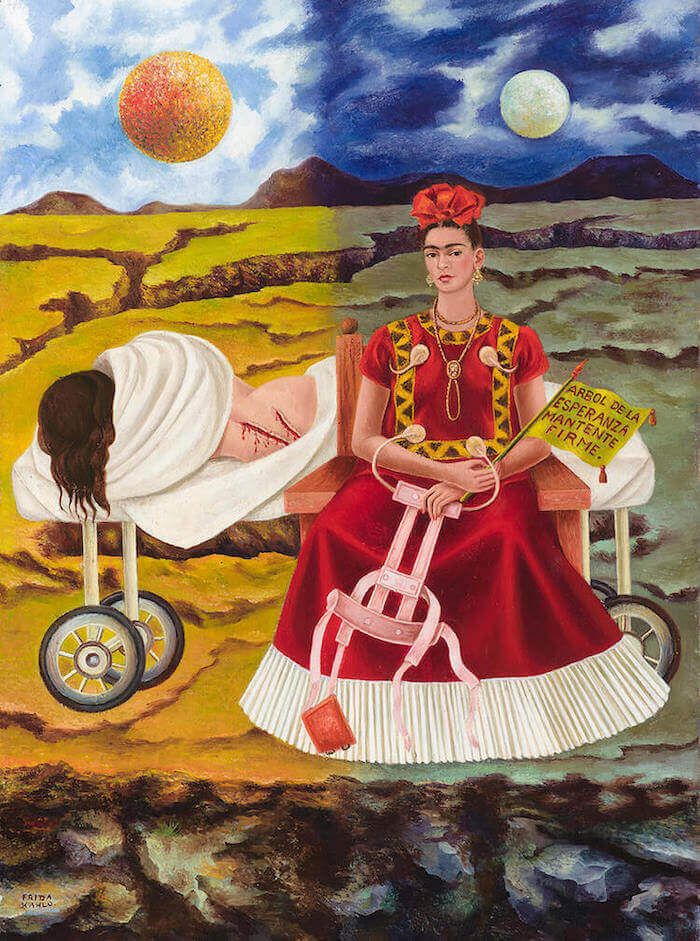

During the 1940's Kahlo's health was declining. This made it harder for her to commute to the school she worked at so many lessons were held at La Casa Azul. Her art also reflects her health. Works such as Broken Column (1944) and Without Hope (1945) perhaps indicate her state of mind and feelings. An attempted surgery to support her spine failed so she spent her final years confined to Casa Azul. The photography Lola Alvarez Bravo recognised the Kahlo did not have much time left, so staged Kahlo's first solo exhibition in Mexico in 1953. Kahlo was not due to attend as she had been prescribed bed rest. However, Kahlo had her four-poster bed moved to the gallery. Guests at the exhibition opening night were astounded when Kahlo arrived in an ambulance and was carried by stretcher to her bed. She stayed there for the duration of the party. An exhibition took place at the Tate gallery the same year, which featured 5 of her paintings.

Nevertheless, Kahlo's health continued to deteriorate and in August 1953 her right leg was amputated because of gangrene. As a result, she became depressed, anxious, and increasingly dependent on painkillers. When her husband, Rivera, had another affair Kahlo attempted suicide but failed. By summer 1954 she was bedridden and approaching her final days. Her last drawing was a black angel accompanied by the words (her last written words) 'I joyfully await the exit - and I hope never to return - Frida'. On 13th July 1954, Frida Kahlo died, aged 47. That night she laid in state at Palacio de Bellas Artes under a communist flag. The following day, at her funeral, hundreds of admirers gathered to pay tribute before her remains were cremated.

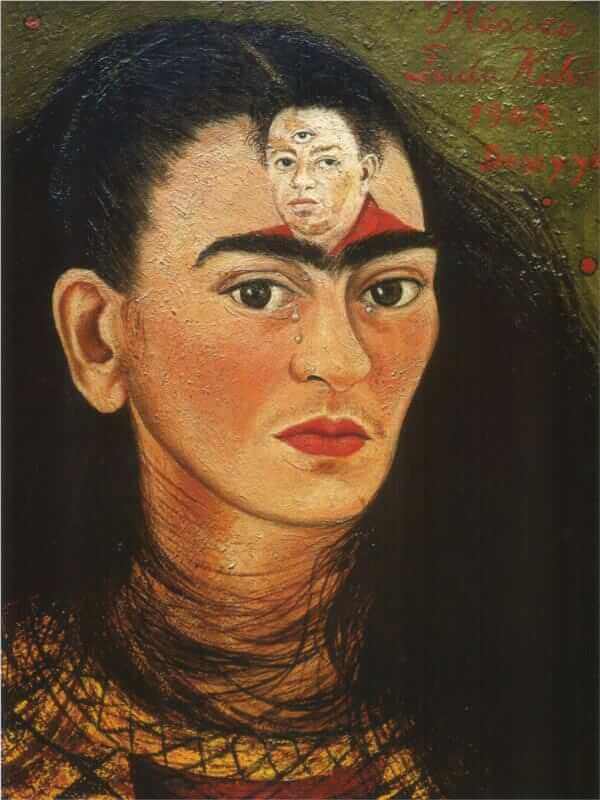

Frida Kahlo is one of many artists who received more appreciation after her life, than she did during it. The Tate Modern described Kahlo as 'one of the most significant artists of the 20th century'. In 1977, her painting The Tree of Hope (1944) was the first of her works to be sold at auction - selling for $19,000 at Sotheby's Fine art auction house. In 1990, she became the first Latin American artist to have a painting sell for over $1 million when her painting Diego and I (1949) sold at Sotheby's for $1,430,000. More recently, in 2016, Two lovers in a forest (1939) sold for $8,000,000. However, it is unlikely that most people recognise her from high end auction houses. Instead, Kahlo has become highly recognisable through her prevalence in popular culture and merchandise. Her artwork graces t-shirts, tote bags, posters, and more. Her distinctive look has been appropriated across the fashion world. Kahlo has become an icon for non-conformity, and this has earned her a place as one of the most iconic and recognisable female artists in the world.

Learn more

Click for Reading List

Gannit Ankori, Frida Kahlo (Reaktion Books, 2013)

Christina Burrus, Frida Kahlo: ‘I Paint My Reality’ (Thames and Hudson, 2008)

Emma Dexter and Tanya Barson (eds.), Frida Kahlo (Tate Publishing, 2005)

Salomon Grimberg, Frida Kahlo: Song of Herself (Merrell Publishers, 2008)

Hayden Herrera, Frida: A Biography of Frida Kahlo (first published 1983; Harper Perennial, 2002)

Hayden Herrera, Frida Kahlo: The Paintings (Bloomsbury Publishing, 1993)

Frida Kahlo, Sarah M. Lowe and Carlos Fuentes, The Diary of Frida Kahlo: An Intimate Self-Portrait (Abrams Books, 2006)

Frida Kahlo and Tina Modotti, Frida Kahlo and Tina Modotti Exhibition Catalogue (Whitechapel Art Gallery, 1982)

Andrea Kettenmann, Frida Kahlo (Taschen GmbH, 2000)

Patrick Marnham, Dreaming with his Eyes Open: A Life of Diego Rivera (Bloomsbury Publishing, 1998)

Martha Zamora, Frida Kahlo: Brush of Anguish (Chronicle Books, 1990)